Endpoints

In one of the previous chapters we have discussed the basic test case structure as we introduced variables and test actions . The

Exactly the same approach is used in Citrus to provide ready-to-use endpoint component for connecting to different message transports. There are several ways in an enterprise application to exchange messages with some other application. We have synchronous interfaces like Http and SOAP WebServices. We have asynchronous messaging with JMS or file transfer FTP interfaces.

Citrus provides endpoint components as client and server to connect with these typical message transports. So you as a tester must not care about how to send a message to a JMS queue. The Citrus endpoints are configured in the Spring application context and receive endpoint specific properties like endpoint uri or ports or message timeouts as configuration.

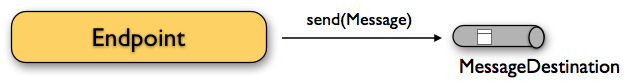

The next figure shows a typical message sending endpoint component in Citrus:

The endpoint producer publishes messages to a destination. This destination can be a JMS queue/topic, a SOAP WebService endpoint, a Http URL, a FTP folder destination and so on. The producer just takes a previously defined message definition (header and payload) and sends it to the message destination.

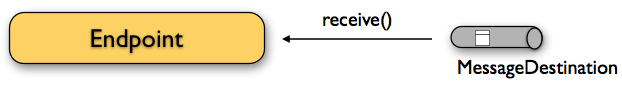

Similar to that Citrus defines the several endpoint consumer components to consume messages from destinations. This can be a simple subscription on message channels and JMS queues/topics. In case of SOAP WebServices and Http GET/POST things are more complicated as we have to provide a server component that clients can connect to. We will handle server related communication in more detail later on. For now the endpoint consumer component in its most simple way is defined like this:

This is all you need to know about Citrus endpoints. We have mentioned that the endpoints are defined in the Spring application context. Let's have a simple example that shows the basic idea:

<citrus-jms:endpoint id="helloServiceEndpoint"

destination-name="Citrus.HelloService.Request.Queue"

connection-factory="myConnectionFacotry"/>

This is a simple JMS endpoint component in Citrus. The endpoint XML bean definition follows a custom XML namespace and defines endpoint specific properties like the JMS destination name and the JMS connection factory. The endpoint id is a significant property as the test cases will reference this endpoint when sending and receiving messages by its identifier.

In the next sections you will learn how a test case uses those endpoint components for producing and consuming messages.

Send messages with endpoints

The

Again the type of transport to use is not specified inside the test case but in the message endpoint definition. The separation of concerns (test case/message sender transport) gives us a good flexibility of our test cases. The test case does not know anything about connection factories, queue names or endpoint uri, connection timeouts and so on. The transport internals underneath a sending test action can change easily without affecting the test case definition. We will see later in this document how to create different message endpoints for various transports in Citrus. For now we concentrate on constructing the message content to be sent.

We assume that the message's payload will be plain XML format. Citrus uses XML as the default data format for message payload data. But Citrus is not limited to XML message format though; you can always define other message data formats such as JSON, plain text, CSV. As XML is still a very popular message format in enterprise applications and message-based solution architectures we have this as a default format. Anyway Citrus works best on XML payloads and you will see a lot of example code in this document using XML. Finally let us have a look at a first example how a sending action is defined in the test.

XML DSL

<testcase name="SendMessageTest">

<description>Basic send message example</description>

<actions>

<send endpoint="helloServiceEndpoint">

<message>

<payload>

<TestMessage>

<Text>Hello!</Text>

</TestMessage>

</payload>

</message>

<header>

<element name="Operation" value="sayHello"/>

</header>

</send>

</actions>

</testcase>

Now lets have a closer look at the sending action. The 'endpoint' attribute might catch your attention first. This attribute references the message endpoint in Citrus configuration by its identifier. As previously mentioned the message endpoint definition lives in a separate configuration file and contains the actual message transport settings. In this example the "helloServiceEndpoint" is referenced which is a JMS endpoint for sending out messages to a JMS queue for instance.

The test case is not aware of any transport details, because it does not have to. The advantages are obvious: On the one hand multiple test cases can reference the message endpoint definition for better reuse. Secondly test cases are independent of message transport details. So connection factories, user credentials, endpoint uri values and so on are not present in the test case.

In other words the "endpoint" attribute of the <send> element specifies which message endpoint definition to use and therefore where the message should go to. Once again all available message endpoints are configured in a separate Citrus configuration file. Be sure to always pick the right message endpoint type in order to publish your message to the right destination.

If you do not like the XML language you can also use pure Java code to define the same test. In Java you would also make use of the message endpoint definition and reference this instance. The same test as shown above in Java DSL looks like this:

Java DSL designer

import org.testng.ITestContext;

import org.testng.annotations.Test;

import com.consol.citrus.annotations.CitrusTest;

import com.consol.citrus.dsl.testng.TestNGCitrusTestDesigner;

@Test

public class SendMessageTestDesigner extends TestNGCitrusTestDesigner {

@CitrusTest(name = "SendMessageTest")

public void sendMessageTest() {

description("Basic send message example");

send("helloServiceEndpoint")

.payload("<TestMessage>" +

"<Text>Hello!</Text>" +

"</TestMessage>")

.header("Operation", "sayHello");

}

}

Instead of using the XML tags for send we use methods from TestNGCitrusTestDesigner class. The same message endpoint is referenced within the send message action. The payload is constructed as plain Java character sequence which is a bit verbose. We will see later on how we can improve this. For now it is important to understand the combination of send test action and a message endpoint.

Tip It is good practice to follow naming conventions when defining names for message endpoints. The intended purpose of the message endpoint as well as the sending/receiving actor should be clear when choosing the name. For instance messageEndpoint1, messageEndpoint2 will not give you much hints to the purpose of the message endpoint.

This is basically how to send messages in Citrus. The test case is responsible for constructing the message content while the predefined message endpoint holds transport specific settings. Test cases reference endpoint components to publish messages to the outside world. This is just the start of action. Citrus supports a whole package of other ways how to define and manipulate the message contents. Read more about message sending actions in actions-send.

Receive messages with endpoints

Now we have a look at the message receiving part inside the test. A simple example shows how it works.

XML DSL

<receive endpoint="helloServiceEndpoint">

<message>

<payload>

<TestMessage>

<Text>Hello!</Text>

</TestMessage>

</payload>

</message>

<header>

<element name="Operation" value="sayHello"/>

</header>

</receive>

If we recap the send action of the previous chapter we can identify some common mechanisms that apply for both sending and receiving actions. The test action also uses the endpoint attribute for referencing a predefined message endpoint. This time we want to receive a message from the endpoint. Again the test is not aware of the transport details such as JMS connections, endpoint uri, and so on. The message endpoint component encapsulates this information.

Before we go into detail on validating the received message we have a quick look at the Java DSL variation for the receive action. The same receive action as above looks like this in Java DSL.

Java DSL designer

@CitrusTest

public void messagingTest() {

receive("helloServiceEndpoint")

.payload("<TestMessage>" +

"<Text>Hello!</Text>" +

"</TestMessage>")

.header("Operation", "sayHello");

}

The receive action waits for a message to arrive. The whole test execution is stopped while waiting for the message. This is important to ensure the step by step test workflow processing. Of course you can specify message timeouts so the receiver will only wait a given amount of time before raising a timeout error. Following from that timeout exception the test case fails as the message did not arrive in time. Citrus defines default timeout settings for all message receiving tasks.

At this point you know the two most important test actions in Citrus. Sending and receiving actions will become the main components of your integration tests when dealing with loosely coupled message based components in a enterprise application environment. It is very easy to create complex message flows, meaning a sequence of sending and receiving actions in your test case. You can replicate use cases and test your message exchange with extended message validation capabilities. See actions-receive for a more detailed description on how to validate incoming messages and how to expect message contents in a test case.

Local message store

All messages that are sent and received during a test case are stored in a local memory storage. This is because we might want to access the message content later on in a test case. We can do so by using message store functions for loading messages that have been exchanged earlier in the test. When storing a message in the local storage Citrus uses a message name as identifier key. This message name is later on used to access the message. You can define the message name in any send or receive action:

XML DSL

<receive endpoint="helloServiceEndpoint">

<message name="helloMessage">

<payload>

<TestMessage>

<Text>Hello!</Text>

</TestMessage>

</payload>

</message>

<header>

<element name="Operation" value="sayHello"/>

</header>

</receive>

Java DSL designer

@CitrusTest

public void messagingTest() {

receive("helloServiceEndpoint")

.name("helloMessage")

.payload("<TestMessage>" +

"<Text>Hello!</Text>" +

"</TestMessage>")

.header("Operation", "sayHello");

}

The receive operation above set the message name to helloMessage. The message received is automatically stored in the local storage with that name. You can access the message content for instance by using a function:

<echo>

<message>citrus:message(helloMessage.payload())</message>

</echo>

The function loads the helloMessage and prints the payload information with the echo test action. In combination with Xpath or JsonPath functions this mechanism is a good way to access the exchanged message contents later in a test case.

Note The storage is for both sent and received messages in a test case. The storage is per test case and contains all sent and received messages.

When no explicit message name is given the local storage will construct a default message name. The default name is built from the action (send or receive) plus the endpoint used to exchange the message. For instance:

send(helloEndpoint)

receive(helloEndpoint)

The names above would be generated by a send and receive operation on the endpoint named helloEndpoint.

Important The message store is not able to handle multiple message of the same name in one test case. So messages with identical names will overwrite existing messages in the local storage.

Now we have seen the basic endpoint concept in Citrus. The endpoint components represent the connections to the test boundary systems. This is how we can connect to the system under test for message exchange. And this is our main goal with this integration test framework. We want to provide easy access to common message transports on client and server side so that we can test the communication interfaces on a real message transport exchange.